Community College Governance

May 1999

Management Audit Committee

Senator Jim Twiford, Chairman

Representative Eli D. Bebout, Vice Chairman

Senator Henry H.R. "Hank" Coe

Senator Keith Goodenough

Senator April Brimmer Kunz

Senator Mike Massie

Representative Deborah Fleming

Representative Randall B. Luthi

Representative Wayne Reese

Representative Colin M. Simpson

Representative Bill Stafford

Staff

Barbara J. Rogers

Program Evaluation Manager

Wendy K. Madsen

Program Evaluator

Kelley C. Pelissier

Program Evaluator

Polly F. Callaghan

Program Evaluator

Don C. Richards

Program Evaluator

Table of Contents

Executive Summary.......................................i

Introduction.............................................................................1

Chapter 1: Background....................................................................3

Chapter 2: Tension in State Community College System Governance..........................15

Chapter 3: Community College System Governance...........................................23

Chapter 4: Community College Funding.....................................................35

Chapter 5: Program Approval, Review, and Termination.....................................45

Chapter 6: Management Information System.................................................55

Chapter 7: Decisions About the College System............................................67

Agency Responses

Wyoming Community College Commission.....................................................69

Casper College...........................................................................73

Central Wyoming College..................................................................76

Eastern Wyoming College..................................................................79

Laramie County Community College.........................................................80

Northern Wyoming Community College District..............................................85

Northwest College........................................................................101

Western Wyoming College..................................................................114

Appendices

(A) Selected Statutes....................................................................A-1

(B) Map of Service Areas and Outreach Sites.......................................B-1

(C) Map of Appointment Districts..................................................C-1

(D) Community College Certificates and Degrees Granted During 97-98 School Year...D-1

(E) Community College Credit Headcount by County for Fall 1997 Enrollment Period..E-1

(F) Higher Education Governance Structures in Other States - 1997.................F-1

(G) Programs Terminated and Approved Between 1994 and 1998........................G-1

(H) Vocational-Technical Programs Offered by Colleges.............................H-1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Community College Governance

Chapter 1: Background and Overview

Wyoming’s community college system consists of seven local college districts and at the state level, the Wyoming Community College Commission. The institutions are located throughout the state, offering instructional programs at their main campuses and, collectively, at 33 out-of-district sites. Since 1991, all 23 counties have been organized into service areas, ranging in size from one to six counties.

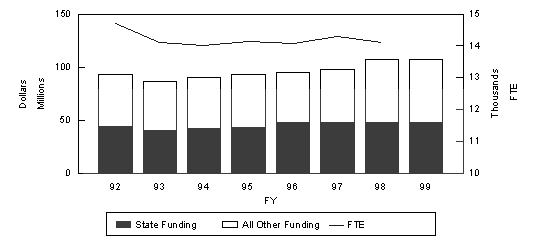

In 1991, after the colleges had been in place for decades, the Legislature established a broad mission for the colleges and directed them to be responsive to the needs of their respective service areas. Each college is a comprehensive community college, offering an array of academic, vocational-technical, basic skills, and non-credit courses. Collectively, for school year 1997-98, 21,579 individuals were enrolled in credit courses. Since students attend primarily part-time, this number is adjusted to reflect an FTE (full-time enrollment) of 14,114 students.

Operating budgets for the seven colleges for the 1999-00 biennium total $216 million, of which approximately $90 million is state-appropriated General Funds. Other revenue sources include tuition and fees, local appropriations, and various federal, state, local, and private grants, contracts, and miscellaneous revenues. According to our calculations, state resources account for between 44 and 63 percent of college operating revenues, depending on which funding is included.

Wyoming statutes set up a two-tier coordination and governance structure, one tier of which is local boards. Local boards have authority to manage their districts. The second tier of governance is the Community College Commission, charged by statute with ensuring "the operation and maintenance of the community college system in a coordinated, efficient, and effective manner."

The seven-member Commission has a staff of 11 and a budget of $2.25 million in General Funds for the 1999-00 biennium. The Legislature appropriates funds to the community colleges through the Commission, which allocates state aid to them through a formula. State aid is given as a block grant with few restrictions.

In the past 15 years, the Legislative Service Office has produced or directed the production of two major reports on the community college system. Both reports essentially recommended increasing the Commission’s coordinating role, and following their release, the Legislature twice enacted statutory changes strengthening that role.

In the nine years since the last major report, the colleges have continued to deliver important services and produce positive outcomes. Nevertheless, at the core of the community college system is fundamental disagreement among participants as to the proper roles of the Commission and local boards. Conflict abounds within this two-tiered system of governance.

Although services may be going on as usual at the individual college level, the governing structure that is meant to coordinate the statewide system (i.e. the Commission) appears to be faltering. At present, we believe the coordinating function operates in a tentative manner, as system participants continue to disagree over who has what authority in what kind of system. Under these circumstances, the Commission’s ability to coordinate the system effectively has been compromised.

The system’s shortcomings have been exacerbated by a legislative history of ambivalence towards state and local control. We believe it is appropriate to look to the Legislature for fundamental policy guidance and clarification of the core issue: Within the state’s mission for community colleges, what are the priorities and desired outcomes, and who will play what role in delivering those outcomes?

Chapter 2: Tension In State Community College System Governance

A two-level debate exists over the governance of the community college system. On one level, the Commission and the colleges disagree over interpretation of the current statutes: the colleges believe the Commission is attempting to overstep its authority, while the Commission believes it is attempting to fulfill its statutory mandate. On the second level, the colleges object that existing Commission authority goes beyond what is appropriate for a coordinating entity, and desire existing law to be changed.

The debate has come to a juncture because both the Commission and the colleges have initiated actions to advance their divergent views on system governance. The Commission has proposed rule revisions that it believes will allow it to more fully implement current statute. The colleges have opposed the rule revisions as well as requested draft legislation to change Commission authority. Currently, the efforts of both are on hold pending the release of this report.

This fundamental disagreement about their statutory roles makes it difficult for the Commission and the colleges to work together to develop a consensus on rules. Rules form the basis upon which the Commission performs its statutory coordinating role. The lack of agreement on them undermines efforts to coordinate community college services.

Over the years, legislative mixed messages have encouraged the conflicting role interpretations among community college system participants. For example, when the Legislature substantially increased Commission authority in 1985, it did not modify the district college boards’ authority to reflect that enhancement. In 1991, the Legislature adopted a mission statement for colleges that focuses them on being comprehensive institutions without implying any roles as part of a system of colleges. In the same legislation, however, the Legislature affirmed the Commission’s charges to make systemwide decisions.

The rule revision disagreement illustrates the tension that has arisen in the community college governance structure. Through the positions they have taken, system participants seem to be appealing to the Legislature to make its position clear in resolving the governance issues. Addressing the various issues over which system participants disagree in an ad hoc manner, however, will not alleviate the overall tension. We believe the Legislature needs to look beyond the specifics of current disagreements to more comprehensively address the tension in the system. This will require it to consider fundamental policies relating to governing higher education institutions.

Chapter 3: Community College System Governance

To address the tension over governance, the Legislature may consider changes either to the current structure or to the allocation of authority within the present structure. Although states are continually revising their higher education government structures, there is an absence of trends in state restructuring. According to the literature on this topic, states approach similar problems with different solutions. This indicates that Wyoming cannot simply import another state’s model.

Instead, state policymakers must first review the broad mission for community colleges to ensure that it reflects current needs and establishes priorities. After affirming or revising the mission, they then should consider whether it can best be carried out by the colleges acting independently, or whether there is benefit to a systemwide approach. With those decisions made, policymakers should review the governance structure to ensure that it supports the colleges, either acting independently or as a system, in meeting state needs.

Currently, the Commission’s role in coordinating community college services to carry out the college mission, as adopted in law, is neither articulated nor broadly understood. The present statutory framework indicates that earlier Legislatures may have wanted a statewide perspective in the governance of the community colleges. However, there is no articulated link between the mission the Legislature assigned the colleges and the Commission’s role accomplishing it. Absent that connection, there is no overall consensus among the colleges about whether the Commission should be responsible for seeing that the colleges collectively act in a coordinated, efficient and effective manner.

Continuum of Governing Structures. As background for a possible legislative review of the community college governance structure, we researched the literature on higher education governance to illuminate the policies implicit in various structure designs. The most generally accepted structures are coordinating board, consolidated governing board, and planning agency structures. However, some experts studying higher education governance find these designations insufficient in capturing the full complexity of state structures. A current trend is to blend these distinct classifications into a continuum of more general governmental organizing principles: federal, unified, and confederated. States create structures that tend to lean more towards one principle than another, but there are no absolutes.The coordinating board or federal approach balances institutional autonomy with a statewide perspective. In this structure, colleges have their own governing boards, and a state-level coordinating board has limited although sometimes significant authority over them. Adopting this approach implies that state elected officials want a state capacity to recognize and respond in an organized and efficient way to state needs, priorities, and contextual changes.

The consolidated governing board or unified system approach establishes a single governing board for either all or segments of a state’s higher education institutions. Under this structure, the consolidated board has legal management and control responsibilities for all the institutions under it. This highly centralized structure most easily avoids program duplication and accomplishes support for statewide objectives. These advantages, however, may be offset by a lack of responsiveness to local needs.

The planning agency or confederated system model may include a weak statewide board with planning and advisory responsibilities. Colleges have their own governing boards which determine individual missions as well as program offerings. Each institution negotiates its budget directly with the governor and the legislature. This structure implies a policy to rely upon the state’s budgetary process to convey priorities and shape institutional responses.

Wyoming statutes provide for a coordinating board structure that reserves some significant policy authority to the state, such as tuition, program, and facility decisions. Statutes and practice also support the planning agency model, with local college boards having significant policy authority as well, including setting their own institutional missions and appointing their chief executive officers. The statutory framework is not clear as to when the authority of one level supersedes the authority of the other. Tension results when these authorities conflict. The literature we reviewed indicates that states should be explicit and unambiguous in delegating authority to avoid conflict.

We conclude in Chapter 3 by suggesting alternatives for modifying the current community college system governance structure. We also pose the following policy questions for the Legislature to consider:

Chapter 4: Community College Funding

Statutes and practices associated with community college funding send mixed messages regarding which level of government, local or state, is in charge. Further compounding that uncertainty, we believe the state has not clearly articulated the purposes for which community college funding is appropriated, nor has it made clear its expectations for desired outcomes.

Statute indicates state funding is intended to supplement local resources. However, aside from this statute, the Legislature provides a sizable amount of funding to college boards to manage without explicit, prioritized, statewide goals.

According to college statutes, district boards retain the authority for the disbursement of all college moneys. In addition, there are several important ways in which the funding strategy is supportive of local control. These include local ownership of college facilities and higher property taxes paid by district taxpayers. College staff salary increases, however, appear to be at least partially contingent upon legislative appropriations. Throughout Chapter 4, we examine numerous ways the funding of colleges influences behavior and shapes college allegiance.

Piecemeal development of the college funding structure likely contributes to these mixed messages. Originally, colleges were totally supported by local funding. However, state resources currently account for 44 to 63 percent of operating revenues, depending on which revenues are included. In the last decade, the Legislature authorized local boards to levy additional mills for the support of community college operations. As a result of this framework, the colleges’ abilities to raise revenue vary dramatically.

Other states have identified similar tensions between funding, authority, and accountability. To address this condition, some states have implemented a performance funding system which uses the budget as an incentive to advance state higher educational goals. Given Wyoming’s investment in the college system of nearly $100 million per biennium, the Legislature may wish to review the policy direction it intends to give community colleges and the level of performance accountability it desires.

Chapter 5: Program Approval, Review, and Termination

The Commission has statutory authority to influence college programs, particularly with regard to duplication, through new program approval, review of existing programs, and termination of programs. However, the Commission has not fully exercised this authority, and it has been of little consequence in shaping or reporting on the overall efficiency and effectiveness of systemwide program offerings.

Program approval is the process whereby an institution submits a proposal requesting authorization from the Commission to start a new program. We found consensus among commissioners, college presidents, administrators, and trustees that regulation of new programs is necessary. Without such regulation, there is a potential for colleges to cause each other harm. There are indications that the Commission performs its program approval function perfunctorily, rather than actively shaping the state’s program offerings with this authority. However, it is likely the existence of an approval process for new programs, in and of itself, curtails proliferation of programs.

Program review is the process whereby existing programs are evaluated. Existing rules establish a deregulated framework for program review, allowing each college to carry out program review in its own way. Lacking specific requirements, colleges have developed program review practices as tools for institutional and program improvement. While this approach to program review may be useful for making institutional management decisions, it does not address questions of systemwide efficiency and effectiveness.

Even the Commission’s minimal level of involvement in program review has not been welcomed by college officials, who believe making program decisions is their role. The Commission is presently developing a more assertive program review process that would assess systemwide efficiency and effectiveness. At this time, it is uncertain if this new process will be implemented, and if it will have a substantial impact on program offerings systemwide.

Program termination is a powerful Commission authority which has the potential to conflict with management authorities given to local boards. The fact the Commission has this authority has created friction. Present rules allow colleges to terminate programs internally and notify the Commission. However, pending rules would change this so colleges could only recommend termination to the Commission.

The legislatively established mission statement for colleges directs them to provide broad, comprehensive programs and easy access for citizens. Statutes also charge the Commission with limiting duplication. These two legislative directives give conflicting messages to local governing boards and the Commission. The result has been an ongoing disagreement between the colleges and the Commission about the rightful role of each with regard to programs.

Without a systemwide program review process, institutional factors at each college tend to drive decisions about program offerings statewide. The fact that half of the vocational-technical programs in the state are offered at only one college is evidence that the colleges do achieve some self-regulation for program duplication. However, a systemwide analysis done by the Commission would likely yield different results than what the colleges generate individually.

Clearly there is a trade-off between efficiency as a system and local choice. Ultimately, system participants need policy direction to evaluate the level of duplication acceptable in the system.

Chapter 6: Management Information System

The Legislature mandated the Commission establish a management information system (MIS) over 14 years ago, yet we found the Commission does not have a comprehensive MIS to provide data about the colleges.

We found that there is not a shared understanding among the system participants of what the statute requires of the Commission regarding data collection. Some system participants believe the Legislature’s mandate to establish an MIS allows Commission staff electronic access to college databases, while others believe the Legislature’s only intent was that the Commission receive data from the colleges.

The Legislature has appropriated about $11 million in the last decade to the Commission for system computing needs. However, the Commission’s data collection efforts have consisted primarily of manual processes, not an electronic database of the college system that can be queried.

Through selected information requests, the colleges do provide certain kinds of data to the Commission. Nevertheless, we found that much of the available data does not, by itself, answer policy questions about college performance. Furthermore, although local trustees receive information about their respective colleges, we found that neither state nor local policymakers are getting comprehensive information about the performance of the colleges as part of a larger system. The Legislature needs to decide if existing reporting provides adequate accountability, or if there is a need for improved information about individual college and collective system performance.

The Commission does not have a comprehensive MIS, primarily due to the conflict over authority between the Commission and the colleges regarding the level of Commission access to college data. Several presidents told us that direct electronic access to college data goes beyond what the Legislature intended when establishing the MIS requirement. College officials also believe that such access would violate federal privacy laws protecting student data.

We also found a lack of agreement and conceptualization about the purpose and implementation of the system. Explicit purposes for data collection have not been well defined. Additionally, the Commission has not built a foundation for data collection at the college level. As a result, the underlying data needed for an MIS is not always being collected at the college level and what is being collected may not be uniform across institutions. College officials told us they would welcome direction in this area from the Commission.

Legislative review should begin with consideration of whether the current state-level and local reporting provide the Legislature adequate accountability for investment in the community college system. Further, the Legislature can clarify whether it desires information about the performance of the seven colleges individually, or if it also wants system-level analysis of college data. Discussion of these questions will bring forward the issue of whether the Commission is an external agency to the colleges or a member of a seamless larger system.

Chapter 7: Conclusion

The struggle over the amount of state and local control in the community college system is not a new issue. During the past two decades, the Legislature and others have expended a great deal of time and money studying community college system problems, but meaningful change has not been realized.

The impasse exists because, over the past 50 years, the Legislature has considered the roles and responsibilities of the various players on a piecemeal basis, and has not clearly defined them within the context of a system. The resulting vacuum has left system participants maneuvering for control.

Through the years, conflicts over governance and structure have largely been left to system participants to sort out. We believe the decisions needing to be made are of a policy nature and cannot be delegated to players in the system. Thus, our recommendations to the Legislature are twofold. First, the Legislature should reassess and prioritize the purpose of the colleges in the state. Second, the Legislature should clearly and unequivocally define the roles of the players within that context.

INTRODUCTION: Scope and Methodology

A. Scope

W.S. 28-8-107(b) authorizes the Legislative Service Office to conduct program evaluations, performance audits, and analyses of policy alternatives. Generally, the purpose of such research is to provide a base of knowledge from which policymakers can make informed decisions.

In September 1998, the Legislature’s Management Council requested that the Management Audit Committee review "the broad issues of the structure and governance of community colleges in Wyoming." The Management Audit Committee accepted the request in October 1998, and directed staff to review the governance structure of the community college system and functional relationships within that system.

Given the breadth of this charge, we conducted a high-level review of the system framework and did not conduct individual program evaluations of each of the seven colleges and the Commission. Rather, we considered issues from the perspective of the statutory framework and its effectiveness.

Our research centered around the following questions:

The purpose of this review was not to evaluate statutory compliance, nor to select the most appropriate way to structure or restructure the system. Rather, we identify policy questions related to community college governance that are in need of clear statutory direction.

B. Methodology

The procedures used to conduct this review were guided by statutory requirements and professional standards and methods for governmental audits. Research was conducted from November 1998 to March 1999.

In order to compile basic information about the college system, we reviewed relevant statutes, statutory history, annual reports, budget documents, strategic plans, a variety of other statistical reports and documents, and selected federal regulations. We contacted long-time observers of the system and we reviewed several analytical reports that have been issued about the community college system over the past 15 years.

We visited each campus and conducted interviews with the presidents, college trustees, and selected administrators. Among other operational aspects, we reviewed each college’s history, mission, budget, and student enrollment data.

To gather information specific to the Commission, we interviewed staff members as well as members of the Commission, four of whom were completing their terms of appointment in February 1999. We did not interview commissioners appointed in March 1999.

We carried out an extensive literature review of professional articles and books on the topic of higher education governance. We also reviewed studies from other states regarding community college system governance. Finally, we conducted interviews with several experts in this field.

C. Acknowledgments

The Legislative Service Office expresses appreciation to those who assisted in this research, especially to trustees, presidents, and staff at the colleges, and to Commission members and staff. We also thank the many other individuals who contributed their expertise.

CHAPTER 1: Background and Overview

Wyoming’s community college system consists of seven local college districts and, at the state level, the Wyoming Community College Commission. Legislation enacted in 1945 allowed for the establishment of colleges; by 1948, four had been founded, while the remaining three were created over the next 20 years. Some began as University outreach centers and some as extensions of their local school district, while others were created by a county-wide vote.

The institutions are located throughout the state, offering instructional programs at their main campuses and, collectively, at 33 out-of-district sites. Since 1991, all 23 counties in the state have been organized into service areas ranging in size from one county (Casper College serves Natrona County), to six counties (Eastern serves Goshen, Platte, Converse, Niobrara, Weston, and Crook Counties). A college must obtain permission from another district before providing services in that service area. See Appendix A for selected statutes and Appendix B for a map of service areas and outreach sites. Figure 1 provides the date the colleges were established and their location.

Figure 1: Wyoming’s Community Colleges

Dates Established and Location

|

Casper College |

1945 |

Casper |

|

Northwest College |

1946 |

Powell |

|

Northern Wyoming Community College District |

1948 |

Sheridan |

|

Eastern Wyoming College |

1948 |

Torrington |

|

Western Wyoming College |

1959 |

Rock Springs |

|

Central Wyoming College |

1966 |

Riverton |

|

Laramie County Community College |

1968 |

Cheyenne |

Source: Wyoming Community College Commission

The Colleges’ Mission

In 1991, after the colleges had been in place for decades, the Legislature established a mission for the colleges. It is to "...provide access to post-secondary educational opportunities by offering broad comprehensive programs in academic as well as vocational-technical subjects. Wyoming’s community colleges are low tuition, open access institutions focusing on academic transfer programs, career and occupational programs, developmental and basic skills instruction, adult and continuing education, economic development training, public and community services programming, and student support services."

In the same legislation, the Legislature directed colleges to be responsive to the needs of their respective service areas. Thus, the Legislature has mandated a wide-ranging set of purposes for the college system.

College District Boards

Wyoming statutes set up a two-tier coordination and governance structure, one tier of which is local boards. W.S. 21-18-304 assigns certain powers and duties to the locally elected boards of trustees, giving them authority to set policies for the management and operation of their individual college districts.

Each seven-member board sets graduation requirements, confers degrees and certificates, collects tuition and fees, and prescribes and enforces rules for its own government. Boards determine their priorities for spending, control and disburse funds, manage their own facilities, and may issue general obligation and revenue bonds for such purposes as construction. Each board also appoints its own chief administrative officer, or president, and determines salary schedules and benefits for its employees.

However, statutes also require the boards to submit reports on their activities as required by the Commission. In addition, the rules of each college must be consistent with rules promulgated by the Commission.

The State Commission

In 1951, when only four of the colleges were in existence, the Legislature created the second tier of governance, the Commission. Prior to that time, there had been no state-level coordinating body. The Commission sees its role as that of providing coordination, advocacy, and accountability for the system.

W.S. 21-18-202(a)(ii) requires the Commission to "adopt rules and regulations which will ensure the operation and maintenance of the community college system in a coordinated, efficient, and effective manner." The statute also requires the Commission to set standards for reviewing the necessity for college districts, and gives it numerous regulatory and administrative authorities.

The Commission has seven members appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the Senate. The appointees serve four-year terms, with a two-term limit. No more than four may be members of the same political party, and no more than three may be from a county with a community college. The Governor and State Superintendent of Public Instruction are ex officio, non-voting members of the Commission.

The Commission office has 11 staff members and a budget of $2.25 million in General Funds for the current biennium. Of this funding, 61 percent is dedicated to support a computer network serving the colleges and the Commission.

Changes in Commission Composition.

Since its establishment in 1951, the Commission has undergone several legislative restructurings. It was constituted originally with 14 members, nearly all from the education discipline, but in 1957, membership was changed to include a resident from each district. In 1971, the Legislature retained district representation but reduced the size of the Commission to nine and forbade membership by a trustee or employee of a district.In 1985, the Legislature again changed the composition of the Commission, this time to its present form. It reduced the size to seven and required representation from statutory appointment districts. Appointment districts are not contiguous with either the college district or service area boundaries. See map in Appendix C for detail. Recent attempts to pass legislation that would require more representation from members who live in college districts have not been successful.

College Programs

Statutes require each college to be accredited academically by the regional accrediting agency. Each is a comprehensive community college, granting both academic transfer degrees and vocational-technical programs. Further, each offers programs that assist citizens who need basic skills before they can successfully approach college level learning. As well, the colleges offer noncredit continuing education programs for career development purposes, and noncredit community service courses.

Systemwide, roughly equal numbers of transfer and vocational-technical degrees are awarded. In school year 1997-98, the colleges awarded a total of 1,748 associate degrees for completion of 60-hour programs in some 31 different areas. The colleges also awarded 269 certificates to individuals who completed 1 of 12 different vocational- technical programs, which are of shorter duration. The certificates and degrees conferred illustrate the emphases colleges have chosen. For example, Northern Wyoming College awards a disproportionately large share of certificates, given its share of enrollment. In contrast, a large share of students at Northwest College received transfer degrees. See Appendix D for detail.

Enrollments

Students in the community college system attend primarily part-time and most often are residents of the county in which they attend college. Nearly the same number of individuals take courses for credit as take non-credit courses.

System data is collected by credit headcount, credit full-time equivalency (FTE), and non-credit headcount. When the term "non-duplicated" is used, it represents an individual student counted one time during the academic year, regardless of how many terms the student attended or how many hours the student took.

Between 1990 and 1997, credit headcount enrollments in Wyoming community colleges declined by 4.7 percent, but credit FTEs increased by 3.3 percent. This means fewer students are enrolled in credit courses, but overall, they are taking more credit hours.

For school year 1997-98, the Commission reported a credit headcount of 21,579, which was an FTE enrollment of 14,114 students. Nearly 65 percent of credit headcount students attended part-time, with more than one-third of the 65 percent enrolled for three credit hours or less.

In noncredit continuing education and community service classes, the system reported a non-duplicated headcount of 21,497. Slightly more than two-thirds of these students were in community service classes, which cover a broad range of topics offered for personal enrichment.

In 1998, Wyoming residents constituted 93 percent of the system’s credit headcount enrollment. More than 60 percent of credit headcount students were enrolled in a community college located in their county of residence. Appendix E shows credit headcount by county of residence.

Funding and Distribution

Operating budgets for the seven colleges for the 1999-00 biennium total $216 million. Operating revenues are a mix of state funding, tuition and fees, local appropriations, and various federal, state, local, and private sources such as grants, contracts, and sales and services of auxiliary enterprises. The two largest sources of revenue for the colleges, state funding and tuition and fees, are described here briefly. In Chapter 4, we describe revenue streams in more detail.

For the 1999-00 biennium, the state appropriated approximately $90 million in General Funds in direct support of community colleges. According to our calculations, state resources account for between 44 and 63 percent of college operating revenues, depending on whether all restricted, auxiliary, institutional, and local resources are taken into account.

Figure 2 illustrates the colleges’ unrestricted operating revenues, which is another accounting method used to describe community college funding. Using this method, which shows the major sources of revenue not restricted for specific purposes, state sources account for about 61 percent of revenues.

Figure 2: 1999-2000 Budgeted Unrestricted Operating Revenues, by Source

Source: LSO analysis of Commission provided data.

The Legislature appropriates funds to the community colleges through the Commission. The Commission allocates state aid to the seven districts through a formula generally driven by the number of FTE and the square footage of facilities within each college. The Commission then distributes funding to the colleges essentially in the form of a block grant, with few restrictions tied to its expenditure.

The colleges currently charge tuition at Commission-set rates of $42 per credit hour for in-state students and $126 per credit hour for out-of-state students. In 1994, the Commission adopted a policy of increasing in-state tuition by 8.5 percent per year for five years, or until Wyoming tuition reaches 90 percent of the average charged by the surrounding states. The last of these increases will apply to the 1999-2000 school year, when tuition will be $46 and $138 respectively.

Colleges also collect fees for certain classes. For the 1999-00 biennium, colleges estimate they will receive, collectively, $33 million in tuition and fees.

Governance: History and Themes

In the 15 years from 1984 to the present, the Legislative Service Office (LSO) has produced or directed the production of two major reports on the community college system. Both reports essentially recommended increasing the Commission’s coordinating role, and following the release of both reports, the Legislature enacted statutory changes.

1984 LSO Management Audit

. In 1984, LSO conducted a sunset review of the Commission to determine the extent to which it had fulfilled its statutory responsibilities. Statutes at that time specified ten criteria for sunset reviews, including whether an agency was operating in an effective, efficient and economical manner. The 1984 study focused on the Commission’s major activities, including new program approval, budgeting, and the distribution of discretionary funding. It also examined community college system governance.The report’s primary conclusion was that the Commission needed to assert a stronger posture in ensuring the colleges’ accountability to the state, since in the 1985-86 biennium, LSO estimated the state provided more than half of the colleges’ funding. As a sunset review, the report discussed what the effect would be, should the Commission be terminated. It concluded that doing so involved making a choice between protecting a statewide interest and promoting local control. It also concluded that the public would suffer if the Legislature were to terminate the Commission without adopting an alternative coordinating arrangement.

Wyoming Community College Code of 1985

. The following year, in 1985, the Legislature made significant changes to the statutes authorizing the community colleges and the Commission (1985 Laws, Chap. 208). These changes, known as the "Wyoming Community College Code of 1985," are largely intact in current statute. In summary, this act restructured the Commission and substantially enhanced its authorities.It was this act that gave the Commission authority to set rules and regulations to ensure the coordinated, efficient, and effective operation of the community college system. In addition, it charged the Commission with reviewing college programs, establishing an effective management information system, and implementing a standardized tuition structure.

1990 Management Audit by Private Consultant

. In 1990, the Legislature appropriated $165,000 for an independent management audit of the internal operations of the community colleges and the Commission. The Legislature also directed that the Commission make $55,000 available for the study. The Legislature required that the work be conducted by a professional independent audit firm and that it cover at least seven specified subject areas, one of which was an analysis of the role of the Commission and its relationship with the colleges. MGT of America, a national firm with expertise in providing consulting services to institutions of higher education, was selected to perform the study.The Management Audit Committee provided oversight for the MGT report, which was completed in late 1990. This comprehensive report presented a statewide perspective, reviewing the seven colleges’ institutional performance within the context of system-wide expectations and statutory directives. The report offered 54 recommendations for actions to be taken by the Commission, the colleges, the Legislature, or by combinations of those actors.

1991 Post Secondary Education Omnibus Act

. Several of the MGT report’s recommendations were enacted into law in 1991 through the "Post Secondary Education Omnibus Act" (1991 Laws, Chap. 228). Under this act, the Legislature established a mission for the community colleges and affirmed its direction for the Commission to fulfill its statutory duties. It directed the Commission to establish and implement an assessment process to evaluate community colleges on the basis of performance in responding to service area needs, based upon an assessment of student outcomes. In response to an MGT report recommendation, the act also increased the staff and appropriation for the Commission.The act called for several additional reports. For example, the Commission was to conduct comprehensive needs assessments of the seven college districts, and the Joint Legislative Education Committee was to develop recommendations for legislation regarding funding of the community college system. The Commission and the University of Wyoming were to submit a report resolving articulation problems, and the Commission was directed to develop a common course numbering system to improve articulation among the colleges and the University.

The act also created a four-year post secondary education planning and coordination council consisting of representatives from the University, community colleges, the Commission, both legislative bodies, and the Governor and Superintendent of Public Instruction or their designees. The council was charged with developing a long-range plan for post secondary education in Wyoming by December 1993.

1990 Joint Reorganization Council Review

. Concurrently with the 1990 MGT management audit of the community college system, the Joint Reorganization Council (JRC) was examining educational issues in Wyoming. In Governor Sullivan’s words, the Legislature established the JRC, in part, "to make government more efficient ... by establishing a clear chain of command so that accountability is assured for the citizens of this state." The Council’s study focused on a goal of enhanced unity and coordination of the state’s post secondary education, and considered various alternatives to Wyoming’s post secondary system governing structure.The JRC, which has since been repealed, recommended an appointed board of regents to serve as a coordinating and central policy body for the state’s postsecondary education system. The recommendation would have abolished the Commission, while maintaining the local community college boards and the university trustees as governing boards for their respective institutions. A bill proposing such a board of regents, which would also have had the authority to approve university and college budget requests, failed to pass the Legislature in the 1991 Session.

Importance of the Colleges

As we conducted interviews during our research, we encountered a generally held impression that the colleges are performing many valuable functions and delivering important services to their communities. Moreover, we became aware of many positive outcomes the colleges are producing. We think it is important to acknowledge some of these outcomes before proceeding to a consideration of the governance issue.

Consistent with the legislatively approved mission statement, system tuition is low and access is high. Data from the American Association of Community Colleges shows that Wyoming’s tuition is about half the national average. According to a recent Commission study, Wyoming community colleges led the nation in percentage of state population served in 1995. Also, data from the colleges and the University of Wyoming indicate that students are able to transfer credits to the University, and after transferring, their academic performance is predictably on par with their peers who started at the University.

As well, University officials told us that the community colleges are extremely important for the overall educational health of the state and for the quality of the workforce. They added that the colleges provide access to students who otherwise would not have that opportunity.

Pressures on the System

Recent research suggests Wyoming colleges may be entering an era of declining enrollments. In Fall 1997, the largest contribution to credit headcount enrollment in the system, 62 percent, came from two age groups: 17 to 24 year-olds, and 40 to 49 year-olds. However, according to the Commission and the Western Interstate Commission on Higher Education, projections for future Wyoming population characteristics bear little resemblance to the trends of the last decade. Predicting a steep decline in these populations beginning around the year 2000, the Commission suggests this shift could negatively impact college enrollments.

We also believe it is important to acknowledge the larger context in which Wyoming’s community college system exists. The broad regional and national context is characterized by numerous trends and pressures which are challenging every state. For example, higher education increasingly finds itself competing for limited state funding against corrections, social services, health, and other human services needs. The technology upon which the colleges depend for both administrative and instructional purposes has many benefits, but is constantly changing and carries with it ever-burgeoning costs. Outside providers such as universities and community colleges from other states are providing competition for Wyoming students.

Controversy About Governance Is Pervasive

Having acknowledged positive performance indicators and disturbing trends, we turn attention to the problem at hand: At the core of Wyoming’s community college system is fundamental disagreement among participants as to the proper roles of the state and the local boards of trustees. It was this disagreement which gave rise to the request for a study of system governance.

Prior to the 1999 Session, the colleges were seeking sponsorship for draft legislation that would have brought to the fore a decades-old conflict between forces favoring local control and those favoring various degrees of state control. College trustees decided to defer action on the proposal pending the release of this study, but the example illustrates the conflict that abounds within Wyoming’s two-tiered system of governance.

Although services may be going on as usual at the individual college level, the governing structure that is meant to coordinate the statewide system appears, to us, to be faltering. At present, we believe the coordinating function operates in a tentative manner, as system participants continue to disagree over who has what authority in what kind of system.

For example, five colleges are suing the Commission over the method of distributing additional salary funding appropriated by the Legislature. According to the Commission’s executive director, "This suit is a test of whether or not the state system functions as a system." In addition, there have been discussions of the possibility of more litigation on the immediate horizon.

Further, in March 1999, the Commission decided to indefinitely suspend its multi-year project of revising rules to make them consistent with its interpretation of statute. For more than a year, the colleges and Commission have been embroiled in an argument over access to college data. This disagreement has delayed Commission research studies and produced one Attorney General’s opinion plus a series of letters to the federal Department of Education in search of resolution. Two of the other areas of disagreement are whether state funds can be used for the maintenance of auxiliary enterprise facilities, and whether colleges must obtain approval from the Commission before constructing or acquiring facilities, even if by gift.

Finally, we observed a great deal of resistance and frustration among system participants that seem to undermine coordination efforts. College representatives expressed a lack of trust in the Commission and a fear that it is moving to exert authority they believe appropriately resides at the local level. On the other hand, Commission representatives expressed frustration over the lack of perceived support for their efforts to carry out their jobs as they believe statute directs them. Under these circumstances, the Commission’s ability to coordinate the system effectively has been compromised.

Solutions Are Legislative In Nature

In its 1984 sunset review of the Commission, LSO wrote: "If Wyoming’s community college system is to continue, the Legislature will need to make some difficult decisions concerning the appropriate relationship between local control and state control." Also, it warned that "the Wyoming Community College system is laced with political overtones of extreme magnitude."

Fifteen years later, these comments are as valid as the day they were written. Because of their fundamentally differing views on any number of questions, the Commission and colleges in 1999 continue to be engaged in disputes that deflect attention and resources from the system’s higher purpose, which is to educate citizens. The Commission and the colleges are developing and testing a number of new approaches having to do with the funding formula, program review, and management information, but it is too early to predict whether the outcomes of these efforts will diminish the controversy.

In the following chapters, we point out that the system’s shortcomings have been exacerbated by a legislative history of ambivalence towards state and local control. The Legislature, in trying to accommodate all views, has created a very broad mission statement for community colleges. However, it is one that provides direction for individual institutions, not for the system statewide. Also, the Legislature has established a statutory framework in which mixed messages abound. The resulting uncertainty about roles and authority undermines the functionality of the system. It also plagues virtually every choice and decision the Legislature faces with regard to community colleges.

Under these circumstances, it is appropriate to look to the Legislature for fundamental policy guidance. Thus, we conclude four of the following chapters with questions, all of which relate to one core issue: Within the state’s mission for community colleges, what are the priorities and desired outcomes, and who will play what role in delivering those outcomes?

The answer, which only the Legislature can provide, will determine the system’s orientation. Once that political decision is arrived at, the message needs to be clearly and consistently articulated in statute so as to eliminate mixed messages and the conflict they engender. After years of discord, we believe such a process is what has the potential to finally bring governance of the community college system to a more effective level of functioning.

CHAPTER 2: Tension in State Community College System Governance

A Two-Level Debate Over Statutes and Authority

Currently, a two-level debate exists in the state over the governance of the community college system. On one level, the Commission and the colleges disagree over interpretation of the current statutes: the colleges maintain that the Commission is attempting to overstep its authorities, while the Commission believes it is attempting to fulfill its statutory mandate. On the second level, the colleges object that existing Commission authorities go beyond what is appropriate for a coordinating entity, and desire existing law to be changed.

In the past, these disagreements did not figure so prominently in the relationship between the Commission and the colleges. System participants say this is because the colleges and the Commission had agreed to an approach to performing their respective roles that mostly sidestepped areas where there were disagreements over authority.

Recently, however, the Commission has attempted to assert the authority it believes it has in these disputed areas. It has done this in part through proposing rule revisions. Although there are many areas of disagreement, we use the rule revision disagreement to illustrate the tension in the community college system. Through its proposed rule revisions and other actions, the Commission has alarmed local college governing boards that view these actions as appropriating their authority. The resulting tension has led to one lawsuit, and it absorbs resources that could be focused upon delivering higher education.

The current situation results from several mixed messages about how the system should be governed, or whether a system even exists. For example, the Legislature established a statutory structure that reserved significant authority to the state, to be exercised by the Commission. The Legislature has also given authority to the college district trustees. However, there is no clear indication of when the authority of one level supersedes the authority of the other level. Further, the legislatively adopted mission statement for the colleges implies that they each should act independently to comprehensively serve their local service areas. This appears to conflict with the role statute assigns the Commission to coordinate a statewide approach to the delivery of higher education at the community college level.

Recent Commission Votes Have Aligned with its Statutory Authorities

In the three-year period (1995-1998) that we reviewed minutes for this study, the Commission took a variety of votes directly related to its statutory authorities. These included decisions relating to:

In addition, the Commission undertook the strategic planning required by W.S. 28-1-115, and made Commission personnel decisions.

The formal actions taken by the Commission during this period nearly always reflected college requests. For example, the Commission routinely awarded requested funds for emergency and preventive maintenance to college facilities, increased budget authorities in response to college requests, approved new programs submitted by colleges, and approved college capital construction plans - sometimes in an expedited manner to meet college schedules.

This limited review reflects what we heard from Commission and college representatives, as well as from system observers, about the Commission’s formal actions. By reaching decisions through a consensus process involving the colleges, the Commission has rarely voted to exert its statutory authorities in ways contrary to college positions. The Commission decision that occurred during the review period to deny a college capital facilities request was reportedly the first denial of that kind. Commission staff said the Commission rarely denied a new program proposal.

Commission Attempts to Assert the Authority It Believes Statute Provides

In the last two years, however, the Commission has begun to position itself to take a more assertive role in system governance. A primary way it has done this is by proposing rule revisions, many of which the colleges adamantly oppose. Since 1997, the Commission has opened 8 of its 13 chapters of rules for revisions and developed a series of policy and procedure handbooks. According to the Commission staff, the objective is to make the rules conform with both statutes and best practices, and to prepare the system to meet future demands. Further, the intent is to make the rules more based on performance. System participants agree that the proposed revisions are significantly different from the rules that are currently in place.

Existing rules date from 1993 and emerged from a consensus process involving the seven college presidents, a trustee, the Commission staff, and a commissioner. Although the group reached consensus on the rules, reportedly neither the colleges nor the Commission were completely satisfied with them. Some college officials believe that the Commission is exceeding its authority in some rules. The Commission staff, however, told us they believe that the compromises reached during this process resulted in rules that do not sufficiently reflect the content and intent of the statutes.

The Commission perspective is that existing rules left the Commission serving only in the capacity of a pass-through agency for system funding. The Commission believes the revisions are necessary to more fully implement statute. College officials, on the other hand, believe the Commission should serve a limited role in the colleges’ operation, primarily one of presenting their unified budget request to the Legislature and disbursing the funding. Further, they would like to see the Commission serve as more of an advocate for the colleges.

College trustees and presidents see the proposed rule revisions as an attempt to expand Commission authority into areas they see as within the purview of the local governing boards. They believe that the Commission has too broadly interpreted its statutory mandate to establish rules to operate the system in a "coordinated, efficient and effective manner." In particular, the colleges oppose the proposed rules with respect to reviewing and eliminating academic and vocational-technical programs. Chapter 5 covers this subject in detail.

Colleges Object to the Commission’s Use of Policies and Procedures

The colleges are also concerned about what is not in the Commission’s rule revisions. The Commission has significantly shortened the proposed rules and has created policy and procedure handbooks to accompany them. The Commission intent behind this approach is to make the rules more succinct and to offer more flexibility in its functions. The colleges’ concern is that these policies would not be subject to public hearing and the consensus process that the system has traditionally used to develop its working relationships. College officials believe that the Administrative Procedures Act (W.S. 16-3-101) requires the Commission to promulgate all substantive dealings with the colleges through rules.

The Impasse Over Rules Undermines Efforts to Coordinate Community College Services

This fundamental disagreement about their statutory roles makes it difficult for the Commission and the colleges to work together to coordinate the delivery of higher education at the community college level. Rules form the basis upon which the Commission performs its statutory coordinating role. College officials do not agree with the rule revisions because they see them as giving the Commission more governing authority than is supported by statute.

Although the existing rules are technically still in effect, the Commission has moved towards practices outlined in the revisions, believing they comport better with statutory directives. Through its staff, the Commission has focused upon performing its statutory responsibilities in a manner that aligns with its interpretation of its role. The Commission recently delayed further discussion and possible actions on the proposed rule revisions pending the completion of this report. However, it will likely eventually adopt revisions, with or without college agreement. Thus, disagreement over the extent of the Commission’s coordinating role is likely to continue.

Also on hold, as noted in Chapter 1, are the colleges’ plans to seek legislative changes that would remove the Commission authorities they see as conflicting with theirs. Notably, they propose to delete the Commission’s authority to implement rules to operate the community college system in a coordinated, effective and efficient manner. In a document explaining their reasons for proposed statutory changes, colleges state that determining measures for effectiveness and efficiency is a trustee role, based upon local needs and institutional missions and goals.

Inconsistent Legislation Encourages Conflicting Interpretations of Roles

Collaboration in drafting the rule revisions has not been possible because the colleges and the Commission interpret statute as giving them conflicting authorities. A series of changes to the statutes setting out Commission authorities and other aspects of the system made over the years has given mixed messages that encourage these differing interpretations. In modifying the statutes relating to the Commission, the Legislature appears to have responded in an ad hoc fashion to political views that prevailed at particular times.

For example, when first giving the Commission authority to approve college programs in 1979, the Legislature countered that increase in power with a statutory requirement that the Commission "be dedicated to the principle of local government for each community college." In 1985, the Legislature substantially increased Commission authority and dropped the specific statutory reference to local control. However, it did not modify the district boards’ authority to reflect the Commission’s enhanced responsibilities. One former state education official characterized the situation as the state having "superimposed a system on top of individually created entities."

Further, the Legislature adopted a mission statement for the colleges in 1991 that focuses them on being comprehensive community colleges. It does not imply that they have roles or responsibilities as part of a system of higher education institutions. In other 1991 legislation, the Legislature affirmed both the colleges’ focus on meeting the needs of their service areas and the Commission’s statutory charges to make systemwide decisions. Such decisions could potentially thwart a local board’s decisions based on local needs.

For more than 30 years, the local boards have had statutory authority to control and disburse, or cause to be disbursed, all moneys received from any source to maintain the community colleges. Yet through the regulatory authorities it has given the Commission, the Legislature has potentially reduced some of the local boards’ discretion in determining how to disburse funds to maintain the colleges. For example, colleges may only operate those programs the Commission approves. Chapter 4 provides a more detailed analysis of how community college funding statutes and strategies have contributed to the mixed messages about governance and authority.

Legislative Ambivalence About the Commission.

Through the stances they have taken, all system participants seem to be appealing to the Legislature to make its position clear in resolving the governance issues. In our interviews of system participants and observers, we learned that there is a sense of legislative ambivalence about the Commission. This sense is most acute among Commissioners and their staff.Although the Legislature voted by a large margin in 1991 to affirm the Commission’s statutory authorities, it is unknown whether that level of support is still present. Only one-fifth of the legislators currently serving were in the Legislature then, although the majority of them supported the legislation (Post Secondary Education Omnibus Act, 1991 Laws, Chap. 228). The general impression of the system participants and observers with whom we talked was that the colleges have greater legislative support than does the Commission. Almost two-thirds of the legislative districts include all or parts of counties that are community college districts.

Colleges Do Not Attribute Legitimacy to the Commission.

College officials are also reluctant to accept what they perceive as a strengthening of the Commission’s responsibilities because they question its legitimacy. College officials indicated a preference to be directly accountable to local constituencies and locally elected boards. College trustees said that because the commissioners are not elected and do not serve as fiduciaries, and also because they do not meet often or necessarily come from college districts, they are less knowledgeable about college needs and less accountable than the local trustees.Roots of Tension Are Fundamental Policy Issues

In this chapter, we used the rule revision disagreement to illustrate the tension that has arisen in the community college governance structure. Although we focus here on rules, there are several other issues over which the Commission and the colleges have conflicts. These conflicts are rooted in fundamentally divergent views on the system’s governance that arise from the mixed messages in statute. To reconcile their differences, both are reportedly seeking legal advice.

An ad hoc approach to addressing the various issues over which system participants disagree, however, will likely not address the overall tension. To more comprehensively address the tension in the system, we believe the Legislature needs to look beyond the specifics of current disagreements and make decisions on more fundamental policies relating to governing higher education institutions. Therefore, in the next chapter, we use a theoretical discussion to illuminate the policies implicit in the design of higher education governance structures. We also offer some policy questions the Legislature might consider should it decide to change or modify the current structure or authorities.

CHAPTER 3: Community College System Governance

One Size Does Not Fit All

To address the tension over governance in the state’s community college system, the Legislature may consider changes either to the current structure or to the allocation of authority within the present structure. As background for such an undertaking, we have researched the literature on higher education governance to illuminate the policies implicit in various structure designs.

A significant body of current literature addresses the topic of higher education governance generally, and some addresses community college governance in particular. Rather than contact states to learn about their individual structures for comparison, we consulted this literature to gain a perspective on how states go about designing higher education governance structures. The literature notes that no single structure or organization is best for every state.

Although states are continually revising their higher education government structures, there is an absence of trends in state restructuring. According to the literature, states approach similar problems with widely different solutions. This indicated to us that Wyoming cannot simply import another state’s model.

Instead, state policymakers must first review the broad mission for community colleges to ensure that it reflects current needs and establishes priorities. After affirming or revising the mission, they then should consider whether it can best be carried out by the colleges acting independently, or whether there is benefit to a systemwide approach. With those decisions made, policymakers should review the governance structure to ensure that it supports the colleges, either acting independently or as a system, in meeting state needs.

The governance structure should also align with the state’s policy environment, which includes factors that current state leaders both affect and inherit. Some might be the relative authority of the executive and legislative branches of state government, the capacity of the state to support higher education, and the state’s political culture and traditions.

Based On Defined Needs, the Legislature Can Determine What the Governance Structure Should Accomplish

A scholar of the governance topic writes that whatever direction a state decides to take in reorganizing its structure, "the purpose of the reforming practices or policies needs to be at the center of public policy decisions." These purposes might include accessibility, quality, affordability, or minimizing bureaucratic controls or political influence on institutions.

Currently, the Commission’s role in coordinating community college services to carry out the college mission adopted in law is neither articulated nor broadly understood. The current statutory framework indicates that earlier Legislatures may have wanted a statewide perspective in the governance of the community colleges. However, in 1985, they created a framework for the system devoid of any real policy objectives other than to be coordinated, efficient, and effective.

The mission statement for the colleges created six years later includes the broad purposes of accessibility, affordability, and comprehensive services. However, there is no articulated link between that mission for the colleges and a Commission role in accomplishing it. As the Commission director noted, "The Commission is not connected to the local boards ... (it) is disconnected in its ability to plan." Absent that connection, it appeared to us that the colleges believe meeting the needs expressed in the mission is an individual endeavor, rather than a systemwide endeavor. There is no overall consensus about whether the Commission should be responsible for seeing that the colleges collectively act in a coordinated, efficient and effective manner.

We believe that several intervening steps should occur before considering changes to the state’s community college governance structure. Policymakers need to review the broad purposes in the community colleges’ mission, and come to understand how those concepts are currently defined in the context of higher education. Then, they should determine if those purposes are adequate or need modification. After those determinations should come consideration of what type of governance structure is needed to accomplish the purposes. And once the Legislature decides upon a structure, it must clarify the roles and responsibilities of each system participant so that governance disputes can be resolved without litigation.

The Continuum of Governing Structures

In preparing this report, we consulted the significant body of literature relating to higher education governance structures. The most generally accepted structures listed by the literature are coordinating board, consolidated governing board, and planning agency structures. We have included a listing of how states employ these structures in Appendix F, which was prepared by Education Commission of the States (ECS). However, some experts studying higher education governance find these designations insufficient in capturing the full complexity of state structures.

A current trend among those studying this topic is to blend these distinct classifications of structures into a continuum of more general governmental organizing principles: federal, unified, and confederated. This results from a recognition of the wide variation and subtle differences in higher education governance structures that reflect states’ different public policy environments. The structures states create tend to lean more towards one principle or another, but there are no absolutes. What follows is a synopsis of what we learned about the continuum of governing structures.

Coordinating Boards (Federal Systems)

This is an approach to governing that balances institutional autonomy (local control) with a statewide perspective. The role of the coordinating board is to function between state government (executive and legislative branches) and the governing boards of the individual institutions. The coordinating board focuses upon planning for the system as a whole to meet statewide needs.

Coordinating functions can include planning and policy leadership, policy analysis and problem resolution, program approval and review, budget development and resource allocation, and maintenance of information and accountability systems. States with this structure assign responsibility for some of these functions to a single agency other than the institutional governing boards.

In this structure, colleges have their own governing boards, and a state-level coordinating board has limited although sometimes significant authority over them. The state reserves for itself only those powers that are necessary to prevent institutions from ignoring statewide concerns. Because coordinating boards may issue regulations and make decisions that have an effect on institutional governance, the lines of authority between governing and coordinating boards are often blurred. According to scholars studying higher education governance in many states under the auspices of the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, because this structure seeks to balance what can be conflicting interests, it typically creates dissatisfaction.

Adopting a coordinating board implies that state elected officials want a state capacity to recognize and respond in some organized and efficient way to state needs, priorities, and contextual changes. It implies a policy of balancing the flexibility institutions need to carry out their individual missions with the statewide planning, coordination, and accountability necessary to meet state needs.

Consolidated Governing Boards (Unified Systems)

States that use this system establish single governing boards either for all degree granting institutions or for different segments of the state’s higher education institutions. For example, a state board of regents might govern all four-year institutions and the community colleges, or a single board might govern all community colleges. Under this structure, the consolidated board has legal management and control responsibilities (including appointing college presidents) for all the institutions under it. Local boards may exist in an advisory capacity.

The institutions governed by consolidated governing boards are more likely to be interdependent, and have common rules and policies that treat students and employees equally throughout the system. Including both two- and four-year institutions promotes effective articulation and transfer policies. A concern with such a structure is that it might devalue the vocational-technical aspect of two-year colleges.

This highly centralized structure implies a policy of systematic, statewide planning for academic or vocational-technical programs and services. It most easily achieves balanced programs without duplication, and accomplishes support for strategic statewide objectives. Advantages in statewide planning capabilities, however, may be offset by a lack of responsiveness to community needs.

Planning Agencies (Confederated Systems)

This type of structure may include a weak statewide board with planning and advisory responsibilities, but it does not have responsibility for actual functions such as information management, budgeting, program planning, or articulation and collaboration. Examples of this structure include a state board of education or a state higher education planning and coordination council.

In these systems, the colleges have their own governing boards which determine individual missions as well as their program offerings. Statewide review procedures are often more a formality than an actual impediment to program duplication. Institutions have separate arrangements for voluntary coordination to identify issues on which they are willing to cooperate when dealing with state government and with each other. Each institution negotiates its own budget directly with the governor and the legislature.

This structure implies a policy to rely upon the state’s budgetary process to convey priorities and shape institutional responses. Statewide planning occurs primarily through voluntary consensus among the institutions or through legislative influence through the budgetary process. Elected state officials have no mechanisms for limiting institutional aspirations, competition, or program and service duplication other than their final authority on the budgets.

Wyoming Statutes Provide for a Coordinating Board Structure

The Commission’s statutory authorities are consistent with those cited by the literature as common to coordinating boards. Further, because the Commission has the substantive authorities to set tuition, make program decisions, and approve facilities, it may be considered a strong coordinating board structure. Previous Legislatures reserved these powers to the state, presumably believing it to be the approach that best protected statewide interests.